Concordia School of Canadian Irish Studies (2009, Montréal, QC)

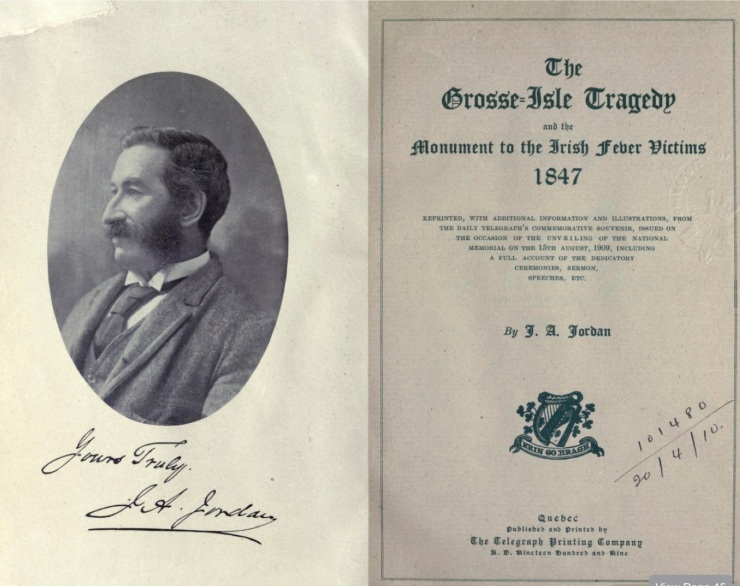

SELECTIONS FROM : The Grosse-Isle Tragedy and the Monument to the Irish fever victims, 1847

(1909, J.S Jordan author, Quebec, Telegraph Prtg. Co.)

As a fit ending to the sad emigration of this season, a more destitute, helpless lot never landed in Canada, penniless, and in rags, without shoes or stockings, without even straw to cover the boards of their bunks.

When the Health Officer at Quebec, Dr. Parent, visited the ship, he noticed three poor children, the youngest about 2 years of age, sitting on the deck, altogether naked, huddled together, and shivering with the cold (for winter had already set in), with a small piece of blanket thrown over them, while the widowed mother sat by without a copper in her possession.

In another place he noticed a young woman whose only article of clothing was made out of the canvas of a biscuit-bag. In fact, in more cases than one, the biscuit–bag was turned to that use.

As for the men, their shreds of clothing were held together with cord.

Irish Famine Orphans in Canada

“No very definite or accurate statistics are available to show the number of the orphaned survivors of 1847. Even an approximate estimate can hardly be made of it, for the helpless children were soon dispersed far and wide, but there is every reason to believe that it ran up into the thousands.

Many of the little ones were taken away from Grosse Isle with them by surviving old country neighbors and friends of the dead parents. Others were taken and cared for by Irish Catholic residents of Quebec, Montreal, etc., or temporarily sent to already existing or rapidly improvised charitable refuges and asylums in those cities.

One devoted priest, Father Harper, rector of St. Gregoire, paid no less than three visits to Grosse Isle, taking away thirty orphans each time and distributing them among his parishioners.

Others again were forwarded to or assisted to reach relatives or friends in the United States. The great majority of the poor Irish Catholic waifs were adopted by the good habitants or farmers in the French Canadian rural districts.

Many of these fortunate children or their descendants have since risen to distinction as citizens of Canada or the United States. Today they are scattered far and wide.

Some of them have preserved and still proudly retain their original family names or Celtic patronymics, but most have lost these or are only known by those of their foster parents, with whose nationality they became identified in every way in feeling, language, etc. In fact, they are as much French Canadian today as if to the manner born. “

** READ FULL BOOK TRANSCRIPT ONLINE HERE

Thousands of Irish children became orphans during the 1847 famine migration to British North America. Read more at Historica Canada’s The Canadian Encyclopedia

1832 | CHOLERA ARRIVES IN CANADA

” In early June 1832, the ship Carricks – arriving from Dublin– is suspected of introducing the first cases of cholera to Canada.”

Introduction of Cholera into Quebec. — The brig Carricks, James Hudson master, sailed from Dublin sometime in April, 1832, with 175 emigrants on board, bound for Quebec.

The cholera, which was prevailing in Dublin at the time of her sailing, broke out among her passengers a few days after she left port ; and before the 3rd of June, the day on which she arrived at Quebec, 42of them ( nearly one-fourth of their whole number,) had died of the disease!

Notwithstanding this, the remaining passengers, amounting to 133, were permitted to land on Grosse isle, a few miles from Quebec, and no rigid measures were adopted to prevent intercourse between them and the inhabi tants of the city.

On the 6th, 7th, and 8th, of June, several cases of cholera appeared in Quebec, and on the 9th, fifteen cases were officially reported. This was the commencement of cholera in the Western Hemisphere ; and Quebec was the starting point from which it proceeded, step by step, to the innumerable places which it has since visited.

Although it is far from certain, the ship Carricks, which arrived from Dublin in early June 1832, is suspected of introducing the first cases of cholera. She had departed the U K with 192 passengers on board and had lost between 42 and 59 individuals to an “unknown disease” during the crossing.

This statement, the authenticity of which may be proved by the reports of the board of health of Quebec, and by the journals of that city ; affords conclusive evidence that the cholera was imported by the brig Carricks.

Contested by ‘anti-vaxers of the era’ (non-contagionists)

The non-contagionists, however, have endeavored to invalidate this fact by urging two objections. One is, that no person had died on board the Carricks for some weeks before she reached Quebec ; the other, that cholera had been prevailing in Quebec for some weeks before her arrival.

The first of these objections, even admitting it to be true, is of but little weight : that forty-two persons died, sometime during the passage, is not denied ; and if cholera may be conveyed at all in fomites, (and there are numerous facts to show that it may,) the opportunity never was better than in a, confined vessel, on board which such dreadful mortality had prevailed.